Advocacy Update: Twin Cities Habitat's Local Priorities

In addition to advocating at the federal and state levels, Twin Cities Habitat for Humanity works to advocate for our affordable homeownership...

5 min read

Blake MacKenzie

:

11:18 AM on February 14, 2020

Blake MacKenzie

:

11:18 AM on February 14, 2020

Twin Cities Habitat has a core value of Equity and Inclusion which states: “We promote racial equity and strive to increase diversity, inclusion, and cultural competency in all aspects of our organization.” We believe it’s important to learn from our national and local history of racist housing policies as we build for the future. This blog series explores the past, offers solutions for the future, and highlights ways you can take action.

If you’ve ever driven on I-94 between Minneapolis and St. Paul, you’ve gone right over the heart of the historic Rondo neighborhood. Before the interstate went through in the 1960s, Rondo was a thriving mostly-black community. In fact, Rondo was home to more black families and black businesses than anywhere else in St. Paul.

That all changed when decision-makers of the day placed the interstate right over Rondo Avenue, ripping the heart out of the neighborhood—even though they had other options. Similar stories played out in other cities as the interstates were built; in Minneapolis, interstates also ran through or cut off redlined neighborhoods.

It was devastating for the community, especially when compounded by other discriminatory policies that came before and continued after.

Nathaniel Khaliq, known by many as Nick Khaliq or Nick Davis, has served as head of the St. Paul NAACP, was a firefighter and interim St. Paul City Councilmember, owned and managed many units of affordable housing, and much more.

Nick at his home in St. Paul.

Nick at his home in St. Paul.

Before any of that, he was a kid growing up in the “cornmeal valley” section of the Rondo neighborhood of St. Paul. His grandfather, Reverend George Davis, and grandmother, Bertha Miller Davis, lived at 304 Rondo—where Nick was born and raised. He loved the neighborhood.

“It was somewhat of a utopia,” Nick remembers. “We had a very loving community. We never felt threatened, never concerned about any harm coming to us. Everybody knew everybody. We had every kind of business you could think of: doctors, dentists, barbers, grocery stores, everything. Most of the black businesses of St. Paul were there. We didn’t need to be bussed to school because there were neighborhood schools that we could walk to. It provided a safety net—everything that we needed to survive and grow up and be productive adults was right there.”

At the time, Nick didn’t realize his family was poor because it was such a tight-knit community where everyone was looking out for everyone. Almost 50% of black folks owned their homes then, compared to less than 25% today. That sense of security was fueled by the fact that you could get a good job with a livable wage without a high school diploma at local businesses like the packing house, Whirlpool factory, and the railroad. Many men chose to work two jobs to afford homeownership, and women chose to stay at home. Rondo felt like a self-contained economic engine.

“Back then, the future was always brighter looking ahead of us than it was the present or what had happened behind us,” Nick remembers. “Unlike today. It’s a lot more questionable.”

Nick was around 13 when I-94 came through. Leading up to construction, he started noticing families moving and businesses closing—slowly at first, then building.

“When I reflect back, I could see the personality and character of the community starting to change because we were losing control over our own destiny. That tight-knit brotherhood and sisterhood was coming apart.”

Nick’s grandfather was 80 years old and felt very passionately that he should not have to lose his home. His home was the last on Rondo Avenue east of Western Avenue.

Nick vividly remembers the eviction. After spending his early years with his grandparents, he was living with his mom at the time. He would still go back to his grandparents' home often—like the day they were forcibly removed from their home.

“I came home that day and saw the big moving truck and saw police cars. I was looking around wondering what was going on. I knew that my grandpa didn’t want to move. I asked, ‘where’s my grandpa?’ When I walked in I saw they were tearing stuff up to make sure he didn’t come back in there. One of the officers said, ‘I’ll take you where your grandparents are.’”

When Nick arrived at his grandparents’ new place, a rental on the other side of town, he found them sitting in the dark. Their look said everything.

“It broke my grandfather’s heart because the only thing I think a black man had back then was his dignity, his pride, self-worth, and independence. He didn’t ask anyone for anything. He was a Pastor, and people in need would come by and he would help them out with prayer, food, or a word of encouragement.”

Despite being a healthy man, Nick’s grandfather died a year later.

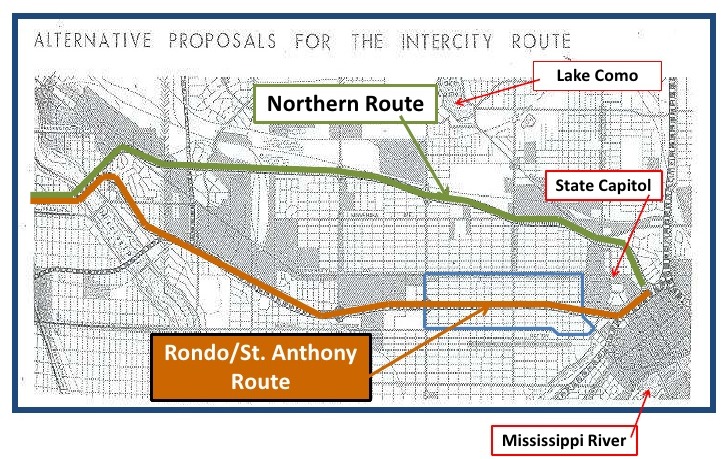

The map above comes from the MN Historical Society's "Uncovering Rondo" slideshow and shows the two main proposed routes for I-94. The area outlined in blue shows the Rondo neighborhood, with the Rondo/St. Anthony route going right through it. The Northern Route along Pierce Butler Road would have been much less disruptive to neighborhoods, but it wasn't chosen.

After being paid pennies on the dollar to get displaced from their homes and businesses, the difficulties didn’t end. Because of redlining and other discriminatory practices, it was almost impossible for families to buy homes elsewhere. Business owners couldn’t find space for their businesses, and most didn’t make it. There was no comprehensive plan or services to help folks relocate. And the built-in social safety net of the community was scattered.

After I-94 displaced so many, next it was “urban renewal.”

“We hadn’t gotten up off the canvas from being knocked down with 94 and then urban renewal came with high hopes that things were going to get better,” Nick says.

Things didn’t get better for many, especially lower-income communities of color who were displaced to make way for other urban renewal developments and gentrification. Many things conspired together to make it so difficult for people of color to buy homes or even stay in one rental for more than a few years.

Nick also didn’t put much thought toward buying a home until an older neighbor encouraged Nick to buy his home from him. At the time, Nick was more interested in buying a car, but eventually he decided he’d look into buying the home. He had been approved for a car loan and went back to the bank to see about getting a home loan instead.

“When I went to them to get a loan close to the same amount as the car, when they looked at the address, they wouldn’t do it. If it happened to me, how many other folks who were trying to purchase homes also got turned down?”

Eventually Nick and his wife Victoria were able to get a home loan from a different bank, but they had to fight for it. Several decades later they still own that home. Nick even reupholstered some of his grandmother’s furniture from the old home in Rondo.

“When we talk about having a fulfilling, successful, and productive life that creates a financial foundation for future generations, I think housing is the key,” Nick says. “Homeownership is the greatest transfer of wealth in this country for anybody and everybody. That was a large piece of our building block for future generations.”

Investing in homeownership is crucial to start to break down some of the racial disparities that were created by government actions like I-94 and redlining. That also means investing in all the steppingstones that lead to homeownership—making sure everyone can have an affordable place to call home where they won’t be displaced by rising rents, new developments, or gentrification.

“It’s going to take folks of goodwill that want for others what they want for themselves and are willing to fight and stand with folks to get it.”

A starting point is to learn from our history. Here are some great resources to help us learn about the Rondo neighborhood and the community spirit that still lives on despite the adversity.

The Days of Rondo by Evelyn Fairbanks

Voices of Rondo: Oral Histories of Saint Paul’s Historic Black Community as told by Kate Cavett

Highwaymen play by Minnesota Historical Theater (MPR interview)

Rondo: Beyond the Pavement documentary by Saint Paul Almanac in partnership with St. Paul Neighborhood Network and High School for Recording Arts

Your gift unlocks bright futures! Donate now to create, preserve, and promote affordable homeownership in the Twin Cities.

In addition to advocating at the federal and state levels, Twin Cities Habitat for Humanity works to advocate for our affordable homeownership...

The end of the year means many things, but a forgotten part is the passage of our city budgets for the new year! Every December, the cities of...

Twin Cities Habitat believes it’s important to learn from our national and local history of racist housing policies as we build for the future. This ...