Mapping Disinvestment & Displacement: A Conversation with Dr. Brittany Lewis

This blog is part of our Race & Housing series. Click here to learn more about this series and why it's important. If you looked at a map of...

3 min read

Blake MacKenzie

:

1:39 PM on December 26, 2019

Blake MacKenzie

:

1:39 PM on December 26, 2019

Twin Cities Habitat has a core value of Equity and Inclusion which states: “We promote racial equity and strive to increase diversity, inclusion, and cultural competency in all aspects of our organization.” We believe it’s important to learn from our national and local history of racist housing policies as we build for the future. This blog series explores the past, offers solutions for the future, and highlights ways you can take action.

Dr. Brittany Lewis is Founder and CEO of Research in Action, an urban research, strategy, and engagement firm that brings in those often left out of decision-making processes to inform research and action. She is also currently a Senior Research Associate at the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs (CURA) at the University of Minnesota. Her recent research in evictions and gentrification has already impacted court decisions and policies. We sat down with her to talk about the legacy of redlining and racism in local housing policy.

Dr. Brittany Lewis.

Dr. Lewis likes to start with a moment in 1953. The Minneapolis City Council was contemplating where to place hundreds of new units of public housing. One option was to build them all near Sumner Homes in North Minneapolis (built in 1938, Sumner Homes was the first public housing in Minnesota with about 400 units and was originally racially segregated). Or, they could scatter them around the metro, bringing public housing to many communities.

The local housing agency urged the council to scatter the units. Some could go as far as suburbs like Maple Grove. This would have prevented a concentration of poverty in one part of the city.

But they chose not to. Why?

“Here’s the reality,” Dr. Lewis explains. “You had members on the council and a number of members from outlying suburban communities who came in and said, ‘You better not do it in my neighborhood.’ And they crumbled under the pressure.”

“It becomes this really powerful example of what racial laws, public policies, and prejudice look like because it’s connected to individual people, and practices, and institutions that are unwilling to stand on their ethics,” Dr. Lewis continues. “There are so many moments like 1953 where we don’t always move our equity-based language into real equity-based action.”

While Minnesota has often projected an almost utopian vision of prosperity for all, black and brown Minnesotans have been kept out of that prosperity through our systems and policies—like the 1953 decision. Concentrating almost all the city’s public housing in North Minneapolis, coupled with discriminatory policies in other parts of the city, left people of color with few choices of where to live. But there’s more to the story.

“We know redlining was happening by the federal government and mortgage companies,” Dr. Lewis points out. The same stories of redlining, blockbusting by real estate agents, and racial covenants were unfolding in cities across the country.

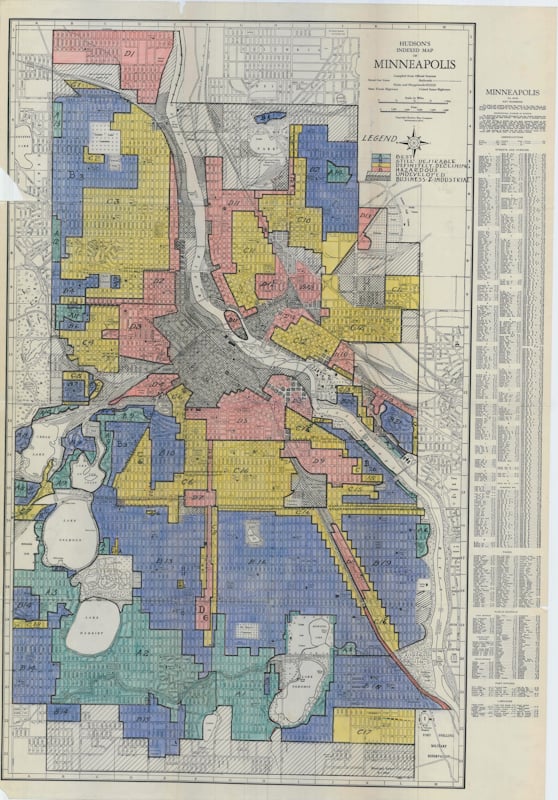

A map of redlining in Minneapolis.

A map of redlining in Minneapolis.

“But,” Dr. Lewis continues, “residents were resisting, and we never get to hear that. Residents right here and across the country were resisting, and they had their own tactics….they wanted a voice.”

The creation of the Northside Resident Redevelopment Council (NRRC) was one of those tactics.

In the late 1960s, the Minneapolis Housing Redevelopment Authority had eminent domain rights in North Minneapolis and was trying to develop the neighborhood, especially after the riots in 1969. A man named Richard Brustad was in charge of the North Minneapolis development area.

Brustad believed development wasn’t going to work unless you involved the community. He had been working with the area’s largely Jewish population, but they were quickly leaving the neighborhood for Saint Louis Park due to blockbusting. He knew he had to build relationships in the black community. Thus, the Northside Resident Redevelopment Council was born.

“NRRC was the first advisory council to a federal housing redevelopment project in the country. Right here in Minneapolis,” says Dr. Lewis.

The neighborhood was divided into districts, and elections were held for folks to sit on NRRC. Community members fought to have their voices heard on federal housing developments in their own neighborhood. According to Dr. Lewis, NRRC was fertile ground for resistance to disinvestment and for growing political power.

“We currently have some of the best funded neighborhoods in the country, and this is part of the beginning of that.”

Van White, the first black Minneapolis City Council member, came up through service with NRRC. Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison, the state’s first black man elected to statewide office, was a volunteer for years with NRRC. Eventually, NRRC turned itself into a community development corporation, building housing, managing properties, and creating other economic development projects.

Van White, the first black Minneapolis City Council member, came up through service with NRRC. Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison, the state’s first black man elected to statewide office, was a volunteer for years with NRRC. Eventually, NRRC turned itself into a community development corporation, building housing, managing properties, and creating other economic development projects.

“All this developed because a housing authority came in to develop land, and they knew they had to work with people,” Dr. Lewis says. “… despite redlining, despite blockbusting, despite these tools of disinvestment, the community found a way to access agency and power to try to reshape some of the politics on the ground.”

This blog series explores the history of racism and disinvestment in housing policies. Too often at critical moments, decision-makers chose a path that didn’t address racial inequities. But Dr. Lewis reminds us that it’s also important to remember and uplift those stories of resistance as models for action today.

“My challenge to people is this: we talk a lot in this state about ethics and the common good. What is that? What does that look like in material reality? We’ve got the language down. But what does action look like?”

Here are some ways you can take action:

Your gift unlocks bright futures! Donate now to create, preserve, and promote affordable homeownership in the Twin Cities.

This blog is part of our Race & Housing series. Click here to learn more about this series and why it's important. If you looked at a map of...

1 min read

This blog was originally published in 2023, and was updated in June 2024. The Open Road Fund is open for applications from June 19 to July 19, 2024....

1 min read

Twin Cities Habitat has a core value of Equity and Inclusion which states: “We promote racial equity and strive to increase diversity, inclusion, and...