Twin Cities Habitat for Humanity has a longstanding relationship with Mapping Prejudice, a project based at the University of Minnesota libraries that has been working since 2016 to uncover the history of structural racism in housing. According to project director Kirsten Delegard, Mapping Prejudice's mission—to dig up and record all racial covenants in Hennepin County—started with a question:

Why does the Twin Cities have some of the highest racial disparities in the nation?

Born and raised in Minnesota, Kirsten reflects on how she was raised on the myth of "Minnesota progressiveness," which feeds the assumption that, as a state, we are on the cutting edge of social justice and progressive policies. With her training as a historian, Kirsten set out to get her facts—and her history—right.

"In terms of disparities – housing jumps out," said Kirsten. "It’s a large disparity, and it’s a foundation for other inequities. Before the covenants, Minneapolis was not segregated at all. The housing segregation that we still see today is not a result of cultural failings or community preferences. It was deliberately constructed this way through covenants."

What is a Covenant?

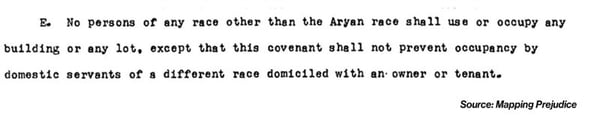

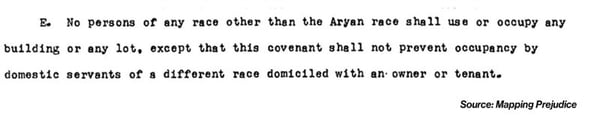

Covenants are contingencies written into documents that have been used to restrict the ways property is used. In theory, covenants are designed to make a property more marketable, attractive, and/or valuable. Examples include the type of building you can build, the cost of a structure, a stipulation saying you can’t have chickens in your backyard, or rules about placing a vegetable garden in your front yard. Basically, they're land use parameters.

Anyone who owns a piece of land and has the money to pay the filing fees and court costs can add a covenant to their land. Many people think of covenants as being similar to zoning restrictions.

By agreeing to buy the property, you sign on to the use of the property. In terms of legal enforcement, covenants are contracts, which would wind up in a lawsuit if a covenant was broken. It was then up to the court system to enforce them.

Racial Covenants

The racial covenants that the Mapping Prejudice project team found in Hennepin County ran with the land—once they’re in the deed, you could never get rid of them, and someone who breached the covenants opened the door to lose whatever they had in the property.

"Racial covenants were one of the most outrageous and shocking practices that made the modern city the way it is," Kirsten said. "I was curious—how widespread were these? Why? What neighborhoods had them? No one had ever figured this out before."

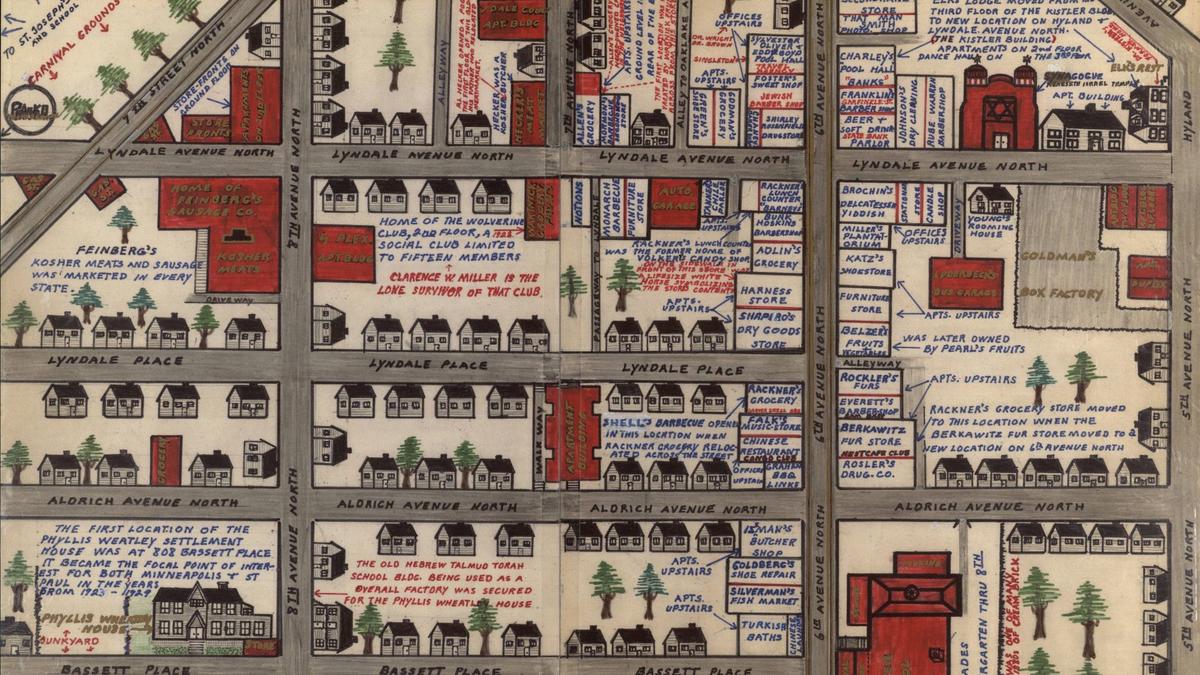

Racial covenants, which prevented people of color from buying or occupying property, started being added to Minneapolis properties at the beginning of the 20th century. Although people were experimenting with racially restrictive covenants before then, that timing is no coincidence.

The first racial convent that has been found in Hennepin County appears in 1910; it correlates with a period of time when cities were rethinking city spaces and shifting to a careful approach that involved more planning of the spaces. Prior to this, cities were developing with little restrictions or infrastructure planning in place.

"Think of things like the separation of factories and homes—roads, playgrounds, garbage pickup. This is the rise of modern city planning," Kirsten said.

During this same time period, the United States was experiencing a nationwide intensification of white supremacy. In the south, there was reconstruction and Jim Crow—a whole series of laws and measures to restrict and create racial hierarchy. These restrictions ranged from barring people of color from owning property to dictating if and when someone could be in certain public spaces. There was a rise in race-related violence, including a very well-known racial riot and massacre in Springfield, Illinois, which prompted the creation of the NAACP.

Digging Up a Buried, Racist Past

"It was very challenging to find the racial covenants at first, because they were buried in property deeds," Kirsten said. "Thus, our comprehensive study was created and we started digging."

"It was very challenging to find the racial covenants at first, because they were buried in property deeds," Kirsten said. "Thus, our comprehensive study was created and we started digging."

To date, Mapping Prejudice has mapped 50,000 racial covenants throughout its work (which includes seven of seven Twin Cities metro counties, as well as Olmstead County; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; North Essex County, Mass.; and Washington, DC).

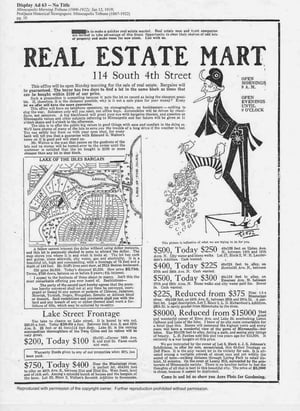

These snippets of racial discrimination tied to properties weren't always as buried as they are now. Developers once prominently published covenants in newspapers and marketing materials. There were also rumors and assumptions made with certain properties and certain locations, which discouraged residents of color from pursuing the purchase of property.

Another maybe lesser-known vehicle for the perpetuation of these racial covenants was real estate agents. Whether or not a property actually had racial covenants in place, they were embedded in the ethics manual for the real estate association, holding agents accountable and prohibiting them from introducing a person of color into a established white neighborhood.

"The real estate profession as a whole is really birthed at the same time as the racial covenants were introduced," Kirsten said. "During that time it was their 'duty' to keep communities racially segregated."

The Discrimination Persists

"Racial covenants combined with federal redlining to drastically depress African-American homeownership rates," Kirsten said. "It was structurally difficult for people of color to acquire property, and consequently, this impacted the accumulation and transfer of inter-generational wealth."

Eventually these discriminatory clauses were brought before the Supreme Court. The following unfolded in the Shelley v. Kraemer 1948 U.S. Supreme court case:

Unbeknownst to both the Shelleys (a black family interested in purchasing) and the Kraemers (the white family selling), the home was subject to a restrictive covenant dating back to 1911 that precluded the use of the property by “any person not of the Caucasian race.” According to the deed, “people of the Negro or Mongolian race” were forbidden from using or occupying the property, or contracting to purchase the property, for a period of fifty years after the original covenant had gone into effect.

While neither party wanted to rescind the agreement, the Marcus Avenue Improvement Association, a local homeowners’ group, filed suit in municipal court demanding the contract for sale be terminated.

As a marker of just how pervasive restrictive covenants had become, three justices were forced to recuse themselves when they learned that their own deeds included such a provision. On January 16, 1948, though, the remaining six justices issued a unanimous opinion vindicating the Shelleys’ struggles.*

While Shelley v. Kraemer made racial covenants unenforceable, people were not willing to get rid of them, and developers kept putting them into property documents. The Minnesota State Legislature reinforced the Shelley v. Kraemer ruling in 1953, making it illegal to put new covenants into housing contracts.

These rulings still weren’t enough.

In 1962, Minnesota passed the Fair Housing Act, one of the first in the country. It was reinforced in 1968 when Congress passed the federal Fair Housing Act, making covenants definitively illegal.

"What's amazing to me is the persistence of the practice once they were established," said Kirsten. "They are the whitest part of the cities today. They don’t budge. And unless you make amends for the wrongs that were done in the past, the patterns will remain the same."

Framing the Future

And the good news is people are trying.

"Habitat is part of an effort to repair that damage," Kirsten said. Habitat's Advancing Black Homeownership initiative was created explicitly to redress the damage done by decades of racist housing practices. The initiative seeks to close the racial gap in homeownership and help more Foundational Black Americans (individuals who are descendants of slavery in the U.S.) with a Special Purpose Credit Program for additional financial assistance, a more flexible mortgage product, and a more intensive pre-purchase coaching program.

Other efforts to reduce homeownership disparities between white people and people of color include down payment assistance programs, and other subsidies and programs built to provide financing to purchase a home affordably.

"We've never pursued the remedies on the same scale that we implemented the restrictions," Kirsten said. "Housing is the primary way Americans accrue wealth. It's also how people are presented with different opportunities and chances to build wealth for their families."

That's why Twin Cities Habitat has taken on our most ambitious affordable housing project to date: The Heights development on the East Side of St. Paul. Located on the 112-acre former Hillcrest Golf Course (itself the product of racially exclusive practices—it was founded by Jewish residents of the Twin Cities who were not permitted to join other golf courses), The Heights will bring 1,000 housing units to the Greater East Side. Habitat will break ground in summer 2024 on what will eventually be 130 to 150 mid-density affordable housing units for low- and moderate-income first-time homebuyers.

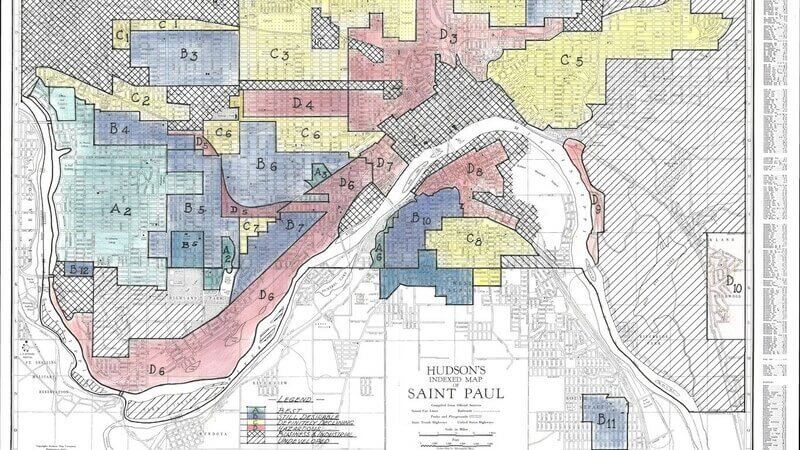

While Twin Cities Habitat is expanding access to affordable housing in St. Paul, Mapping Prejudice continues their work in the area. Michael Corey, the project's Associate Director and technical lead, said they have mapped 5,600 modern properties in Ramsey County that had a racial covenant on them. "We actually have a fair number of covenants on the East Side," he said. "We typically see them in neighborhoods that were at the time (mainly 1920s through 1940s) attainable housing for middle-income families."

Some good news: communities are by and large supportive of the effort to bring attention to racial covenants. "We've taken great care to build community coalitions," Michael said. "Our volunteers are our biggest asset: they feel ownership of the work. People have reached out organically. The key is to find partners to do community engagement to get volunteers."

Twin Cities residents who want to research the history of their own property can do so on Mapping Prejudice's interactive map. A number of cities and counties around the metro area offer residents free help in discharging a racial covenant, should they find one on their property, including Minneapolis and St. Paul. To get involved with Mapping Prejudice as a volunteer, Michael recommends signing up for a transcription session.

The work of Mapping Prejudice and of Twin Cities Habitat is expanding. But transforming our state's racist history starts with education. "You have to remember this history and learn about it. It's not going to be one program that changes this. We have to be rethinking the way we understand housing through the lens of this history and racial disparities. If you remember the history, you can’t look at anything the same, and the 'status quo' is no longer acceptable."

To learn more about the Twin Cities' racial disparities and history of discrimination, subscribe to our blog and keep following this series!

*Excerpt from https://constitutioncenter.org

"It was very challenging to find the racial covenants at first, because they were buried in property deeds," Kirsten said. "Thus, our comprehensive study was created and we started digging."

"It was very challenging to find the racial covenants at first, because they were buried in property deeds," Kirsten said. "Thus, our comprehensive study was created and we started digging."