Race and Housing Series: Housing and Heart Health

This blog has been updated to include information about a recent Twin Cities Habitat event. On Thursday, October 7, Twin Cities Habitat hosted the ...

Twin Cities Habitat for Humanity has a core value of Equity and Inclusion which states: “We promote racial equity and strive to increase diversity, inclusion, and cultural competency in all aspects of our organization.” We believe that it’s important to learn from our national and local history of racist housing policies as we build for the future. This blog series explores the past, offers solutions for the future, and highlights ways that you can take action.

Have you ever gone for a walk on a hot day, and suddenly realized that you somehow felt cooler than you did ten minutes ago, despite moving around? You may have crossed into a new neighborhood from an urban heat island (UHI). And despite what it sounds like, it’s not all paradise.

What is an urban heat island, exactly? According to the National Geographic Encyclopedia, an UHI is “a metropolitan area that's a lot warmer than the rural areas surrounding it.” This is largely due to the result of trees and greenery being removed (which filter and cool the air) in order to replace them with buildings and roadways (which reflect the sun to warm the air).

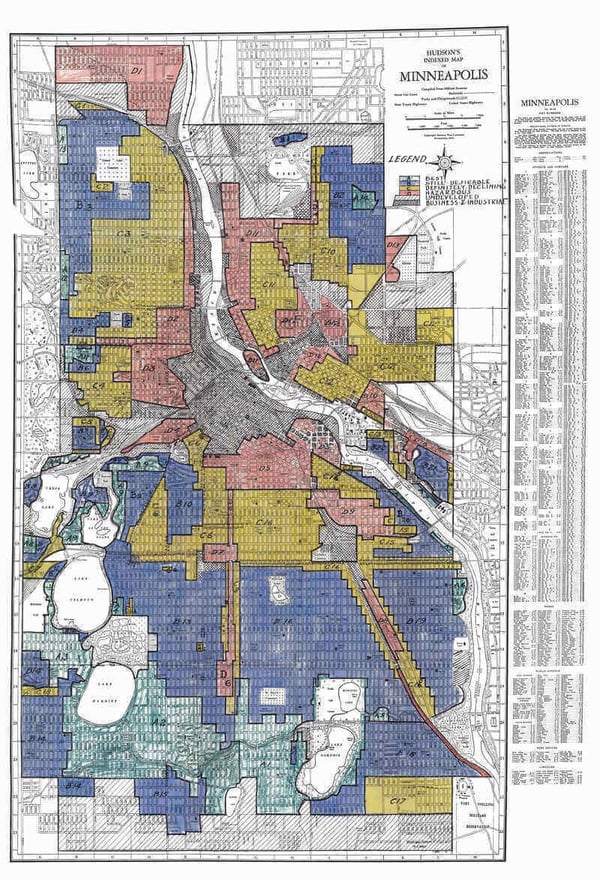

You might notice that neighborhoods which seem to be warmer in the summer also tend to be lower-income neighborhoods. This isn’t a coincidence, but a result of redlining. The history of redlining is defined as “a discriminatory practice by which banks, insurance companies, etc., refuse or limit loans, mortgages, insurance, etc., within specific geographic areas, especially inner-city neighborhoods.” (Learn more about redlining and other discriminatory practices at our Race & Housing Resource Center.)

These practices raised interest rates for people of color and recommended that white people avoid buying in areas that were “redlined,” literally outlined in red if a single family of color lived there. This created a cycle of disinvestment in communities of color, resulting in a lack of both funds and political clout that were required to plant and maintain trees and other green spaces. It also lowered property values so much that these areas became attractive to companies that wanted to build factories and other industrial facilities, which led to the elimination of existing trees, adding more concrete, and increasing air pollution in these already disadvantaged communities.

These practices raised interest rates for people of color and recommended that white people avoid buying in areas that were “redlined,” literally outlined in red if a single family of color lived there. This created a cycle of disinvestment in communities of color, resulting in a lack of both funds and political clout that were required to plant and maintain trees and other green spaces. It also lowered property values so much that these areas became attractive to companies that wanted to build factories and other industrial facilities, which led to the elimination of existing trees, adding more concrete, and increasing air pollution in these already disadvantaged communities.

Redlining, and the resulting lack of greenery in formerly redlined neighborhoods, has affected temperature differences in distinct and measurable ways.

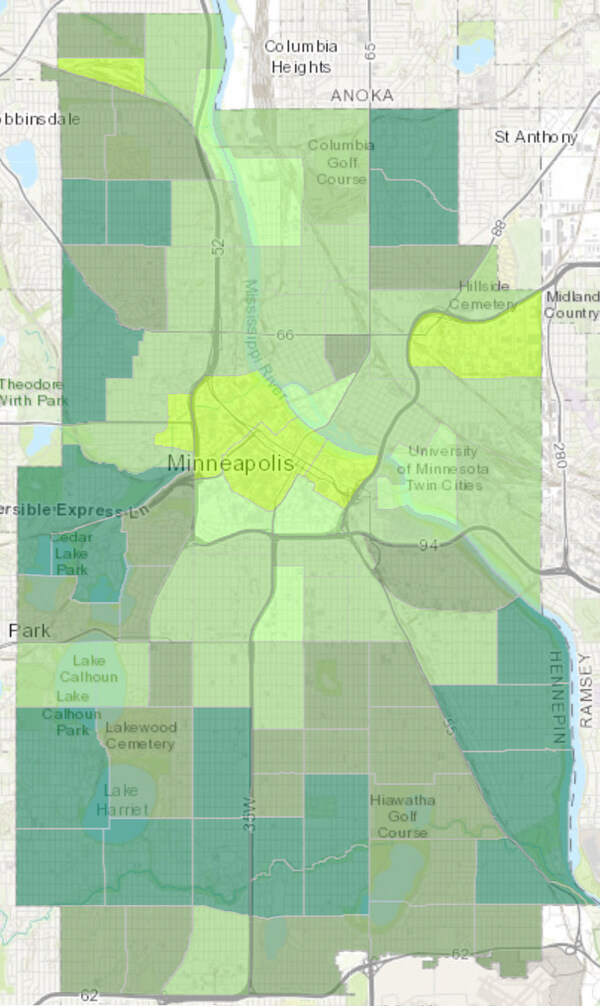

Tree canopy, or the amount of the city that is covered in shade, varies drastically depending on where you are. An analysis of 37 metropolitan areas found that formerly redlined areas have an average of around 23% tree canopy cover, compared with approximately 43% tree canopy cover in areas previously restricted to all-white populations. Similarly, University of Minnesota's Remote Sensing and Geo-spatial Analysis Laboratory Department of Forest Resources built the Minneapolis Urban Tree Canopy tool, which provides a clear look at how the tree cover in Minneapolis still generally follows the shape of disenfranchised neighborhoods.

Tree canopy coverage in Minneapolis - lighter green = less coverage

According to an analysis of University of Minnesota data, areas with predominantly white residents experience weather that can be cooler by double digits on hot summer days. And at night, these differences can feel be even more stark – residents in hotter areas don’t get the same relief after the sun goes down during heat waves, exacerbating existing health conditions.

Taking a look at the Metropolitan Council’s Extreme Heat Map Tool, we’ll see that apartment-dwellers living in industrial areas in the Twin Cities metro area can experience up to 125 degree temperatures during the summer. For reference, according to the National Weather Service a heat index of 103 degrees is dangerous (a heat index is the combination of air temperature and humidity, and is always higher than the air temperature). Most of these industrial zones are deep in historically redlined areas.

Heat makes everyone uncomfortable, of course, but the health effects of high heat are more significant than most people know. The National Institutes of Health say that for every 1°F increase in heat wave intensity, heat wave mortality risk increased 2.49%. Being unable to find a place in the shade to rest on a hot day can have deadly consequences.

Statistics from Baltimore in 2018 illustrate a deeply concerning landscape for those with pre-existing conditions. When temperatures reached 103 degrees, EMS calls for high blood pressure doubled. In addition, calls for cardiac arrest increased by 80%, COPD by 70%, and respiratory distress by 20%. Many other conditions were exacerbated by the heat.

It’s not just heat alone that can cause health problems. Increased heat and sunlight can combine with pollutants put out by cars and industrial plants to cause a chemical reaction that causes higher levels of ground-level ozone pollution and lower air quality. Health problems caused by this effect are far more likely if you live close to a major roadway – and many of those areas already have fewer trees than surrounding neighborhoods.

There are many ways to help alleviate excessive heat and air pollution in UHIs. An example of one of these strategies is to plant vegetation as barriers near highways and other high-concrete areas.

Another is to develop community gardens, which offer a place to get out of the heat, socialize with neighbors, and learn new skills. The Minneapolis Parks & Recreation Board adopted a Community Garden Policy in 2018 that will expand community garden accessibility across the city.

Funding for parks is also crucial, as the historical disinvestment in redlined neighborhoods has led to parks with sparse trees, few renovations, and a lack of government support. In 2015, three neighborhood parks in North Minneapolis received less than $25,000 in funding, while in Southwest Minneapolis not a single park received less than $150,000.

Soon after, two new ordinances were passed to create new systems to allocate funds to both neighborhood and regional parks in Minneapolis. These systems use data-driven criteria to address economic and racial equity in funds allocation. As a result, parks that were previously receiving significantly less funding than parks in wealthy neighborhoods are now receiving more equitable amounts of funding to use toward park rehabilitation and development.

At Twin Cities Habitat for Humanity, we’re doing our part to keep families cool:

All of these help to lower cooling costs for homeowners, allowing them a place to get away from the heat on sweltering summer days.

As we move forward to undo the disastrous effects of redlining, it’s important to keep in mind how we got here, and how it’s affecting people right now. As the climate heats up year after year, keeping every neighborhood cool will become even more critical. Looking to our past offers critical lessons about what we’ve done wrong, and what we need to do better.

If you share our vision of an equitable Twin Cities region where all families have access to the transformational power of homeownership, please join us as a volunteer and subscribe to our blog to keep up with ways to take action.

Your gift unlocks bright futures! Donate now to create, preserve, and promote affordable homeownership in the Twin Cities.

This blog has been updated to include information about a recent Twin Cities Habitat event. On Thursday, October 7, Twin Cities Habitat hosted the ...

Twin Cities Habitat has a core valueof Equity and Inclusion which states: “We promote racial equity and strive to increase diversity, inclusion, and...

This blog is part of our Race & Housing series. Click here to learn more about this series and why it's important. If you looked at a map of...