Race & Housing: The Racialized Impact of Student Loan Debt on Homeownership and Wealth Building

Guest Blog by Shoreé Ingram, Director of Equity and Inclusion There is an old adage that says, “When America gets a cold, Black folks get the flu.”...

Twin Cities Habitat has a core value of Equity and Inclusion which states: “We promote racial equity and strive to increase diversity, inclusion, and cultural competency in all aspects of our organization.” We believe it’s important to learn from our national and local history of racist housing policies as we build for the future. This blog series explores the past, offers solutions for the future, and highlights ways you can take action.

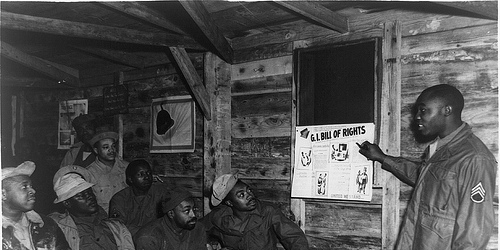

To thank and support the 16 million Americans who served during WWII, America passed the GI Bill. It offered veterans affordable money to go to college, start businesses, and buy homes. In all, 2.5 million families bought homes. Almost all of them white.

This result was likely the goal for some of the lawmakers who crafted the GI Bill. One critical vote came from Congressman John Rankin from Mississippi. Rankin was openly pro segregation: he had proposed a federal law banning interracial marriages, he called for the deportation of Japanese Americans, he opposed laws meant to stop lynchings, and he supported poll taxes which prevented blacks from voting in the south. To win Rankin’s support, the GI Bill required that state and local governments be able to oversee how benefits were handed out. This ensured Jim Crow laws and policies would play out across the country.

The Veterans Administration also helped craft the GI Bill at a time when its housing and hospitals were still segregated. The problems created by the Federal Housing Administration’ mortgage redlining in the 1930s were carried forward via the GI Bill because it relied on the same maps to determine where mortgages could be insured, and therefore offered.

The Veterans Administration also helped craft the GI Bill at a time when its housing and hospitals were still segregated. The problems created by the Federal Housing Administration’ mortgage redlining in the 1930s were carried forward via the GI Bill because it relied on the same maps to determine where mortgages could be insured, and therefore offered.

For many blacks, the promises of the GI Bill were immediately broken because they were dishonorably discharged from the service at much higher rates than whites following the war. This made them ineligible for benefits.

For blacks who were eligible, Jim Crow hindered them at every step and examples abound nationwide.

In Mississippi, a survey of 13 cities found that only 2 of the 3,229 VA loans offered in 1947 went to black homebuyers.

In New York and northern New Jersey, 67,000 families purchased homes with the GI Bill and only 100 were non-white families (roughly 10% of WWII veterans were non-white). The developer of Levittown, a new suburb built in Pennsylvania, refused to sell homes to black families. The town had grown to 70,000 people by 1953.

One black veteran wrote on a survey: “I was required to make a 10 percent down payment because I was told that colored G.I.s were a bad risk.” The GI Bill explicitly said veterans didn’t need to make down payments.

One black veteran wrote on a survey: “I was required to make a 10 percent down payment because I was told that colored G.I.s were a bad risk.” The GI Bill explicitly said veterans didn’t need to make down payments.

Jackie Robinson, a WWII veteran who went on to break baseball’s color barrier, even ran into racism trying to buy a home in New York in 1956. He’d led the Brooklyn Dodgers in winning the World Series the year before, but testified before Congress in 1959 about the struggles his family faced in home shopping:

"At first we were told the house we were interested in had been sold just before we inquired, or we would be invited to make an offer, a sort of a sealed bid, and then we'd be told that offers higher than ours had been turned down. Then we tried buying houses on the spot for whatever price was asked. They handled this by telling us the house had been taken off the market. Once we met a broker who told us he would like to help us find a home, but his clients were against selling to Negroes. Whether or not we got a story with the refusal, the results were always the same."

The Robinson family ultimately ended up buying a home across the state line in Connecticut.

“This nation throughout its history has been more willing to fight a war for democracy than to actually practice it,” said Jesse Dedmon, Jr, who was a Harvard-educated veteran and became the NAACP’s director for Veterans Affairs starting in 1944.

The GI Bill was intended to be a pathway to the middle class for all, but it ended up reinforcing racist housing policies and inequities that were well entrenched by the 1940s. The overall homeownership rate in America rose from 44% in 1940 to 62% by 1960, while the black homeownership rate rose from 23% to 42% during that time.

The homeownership benefits of the GI Bill came to be just as new suburbs were developing – often with stipulations that blacks could not buy homes in them.

The effects are still being felt today. The homeownership rate for white families has slowly climbed to 69% in America but remains at 42% for blacks – the same as it was 60 years ago.

The Twin Cities numbers are even worse (among the worst in the nation). The current homeownership rate for white families is 75% and for black families it’s 25%.

Homeownership has been the driving force for wealth creation in America over the past 60 years. It offers several advantages over renting: mortgages payments can essentially be locked in for 30 years, while rents will rise steadily over that time; the mortgage interest deduction gives families a significant tax break each year; and home values have risen faster than inflation. In addition, a home is an asset that is easily passed from one generation to the next.

These benefits compound and grow with time. The result is that today’s white families in America have an average of $139,300 in wealth, compared to $12,780 for the average black family. This disparity reflects a similar wealth gap between homeowners and renters. The Federal Reserve studies this and found in 2018 the average homeowner had $231,400 in wealth versus $5,200 for the average renter (which is actually down from $5,500 in 2013).

In future blogs we'll explore ways we can work together to unwind the systemic racism that created today's housing and wealth gaps. Until then, please join Twin Cities Habitat in this effort. A simple 30-second step you can take right now is to sign onto our Cost of Home campaign. Cost of home is a five-year nationwide Habitat advocacy campaign to improve home affordability for 10 million people. By signing on, you'll receive action alerts with simple steps you can take to support affordable housing policies. You'll help undo the legacy of housing discrimination.

Your gift unlocks bright futures! Donate now to create, preserve, and promote affordable homeownership in the Twin Cities.

Guest Blog by Shoreé Ingram, Director of Equity and Inclusion There is an old adage that says, “When America gets a cold, Black folks get the flu.”...

Minnesota and the Twin Cities regularly rank highly on quality of life measures. However, both are also notable for the level of racial disparities...

Every person who wants to become a homeowner has a different reason to pursue this dream. Some want the stability that comes with knowing you won’t...