Race and Housing Series: Redlining and Resistance – An Interview with Dr. Brittany Lewis

Twin Cities Habitat has a core valueof Equity and Inclusion which states: “We promote racial equity and strive to increase diversity, inclusion, and...

4 min read

Blake MacKenzie

:

8:30 AM on January 20, 2021

Blake MacKenzie

:

8:30 AM on January 20, 2021

This blog is part of our Race & Housing series. Click here to learn more about this series and why it's important.

If you looked at a map of Minneapolis unfolding over time, you’d see waves of demographic changes sweeping across the city. You’d see large sections of the city that are affordable to lower income folks shrink and then disappear. Zooming in on North Minneapolis, you’d see neighborhoods of Jewish immigrants moving in and then out, followed by Black families. You’d see evictions and foreclosures spike during the 2008 recession, but in only a few spots. You might wonder: why?

Dr. Brittany Lewis can help us understand why displacement happens and what we can do about it. She is Founder and CEO of Research in Action, and is also a Senior Research Associate at the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs (CURA) at the University of Minnesota. I spoke with her last year about the legacy of redlining and racism in local housing policy, and the stories of resistance. Today, we’re revisiting that conversation and exploring Dr. Lewis’ research into gentrification and evictions.

Dr. Brittany Lewis.

Dr. Brittany Lewis.

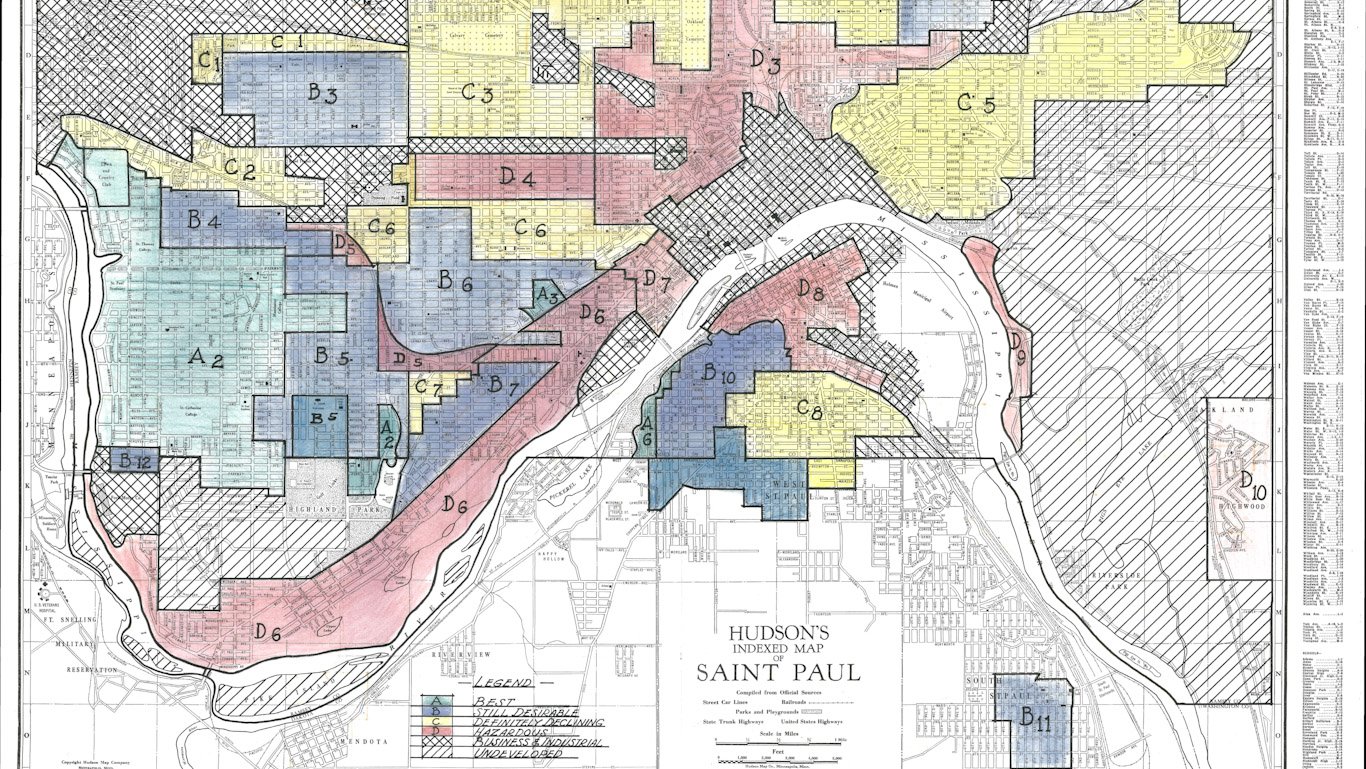

There is a long history of disinvestment in Black neighborhoods. It includes policies like racial covenants on homes, redlining, insufficient funds for affordable housing, and on and on. But Dr. Lewis invites us to think about disinvestment in a different way.

“Disinvestment goes beyond policy,” she says. “It’s a disinvestment in people and what we believe in people…When we think about disinvestment, I challenge people to go beyond policy and practice to talk about racial prejudice. How we assume that someone deserves something more than another person.”

Dr. Lewis shares a helpful example of this type of disinvestment: the opioid epidemic of the 2000s vs. the crack epidemic of the 1990s. The crack epidemic was portrayed as an inner-city Black issue, while the opioid epidemic was portrayed as a rural White issue. The crack epidemic was met mostly with policies of criminalization; the opioid epidemic met mostly with policies of rehabilitation.

It’s the same story for housing.

“Disinvestment goes beyond the bricks and mortar,” Dr. Lewis says. “It goes into how we’ve associated certain characteristics with communities… Systems have embraced the notion that proximity to Black people is a problem.”

It’s a vicious cycle we seem to be trapped in: disinvestment in Black communities leads to poorer living conditions in Black communities, which policymakers use as justification for further disinvestment in Black communities. And this cycle of disinvestment based on our history of racist housing policies has become enmeshed in everything.

You can draw a clear line from this cycle of disinvestment to many things, including gentrification. In the 1970s and beyond, White flight out of the cities, coupled with defunding government programs like public housing, left cities increasingly reliant on private funding. And new development means new revenue—even if it’s displacing people in the process.

“Gentrification was going to happen,” Dr. Lewis explains. “The question is: are cities willing to put mechanisms in place to hold people accountable to making things accessible and affordable?”

Dr. Lewis partnered with the Equity in Place Table to examine how gentrification was happening in several Twin Cities neighborhoods. She also interviewed residents to see how their lived experiences reflected the data on gentrification. The results were fascinating.

“The pockets of gentrification are happening very differently even with communities that are adjacent to one another because of the politics of urban disinvestment. Northeast and North were developed very differently. They’re both gentrifying at different rates and in drastically different ways. That was a fascinating find for us, because in the national conversation gentrification has one look—a common narrative.”

Learn more about the gentrification study here >

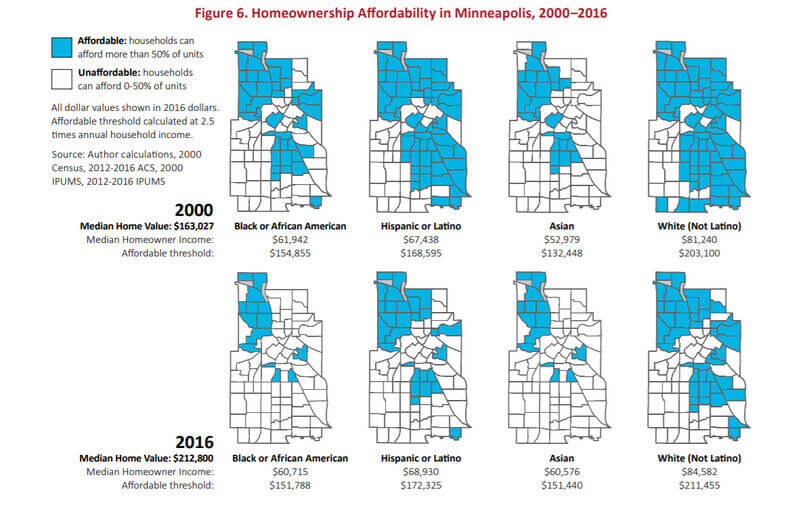

The chart above is from The Diversity of Gentrification: Multiple Forms of Gentrification in Minneapolis and St. Paul by Edward G. Goetz, Dr. Brittany Lewis, Anthony Damiano, and Molly Calhoun, published by the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs (CURA). It shows how homeownership in Minneapolis has become increasingly unaffordable from 2000-2016, especially for people of color. Essentially, the city is shrinking for lower-income folks.

What’s happening in Northeast Minneapolis resembles a more typical picture of gentrification. While the designation of the Northeast Arts District was meant to protect the raw artists living and working there, it inevitably led to more development (and capital) for the city. Working class White folks were displaced.

In North Minneapolis, gentrification looks different. Residents experience a lack of community-based development in favor of new developments that extract capital from the neighborhood. In the Homewood neighborhood of North, some neighbors are pushing for historical preservation to maintain the character of the neighborhood. But this is causing others to worry that the increased costs of historical preservation will displace more families.

Unfortunately, eviction can be a consequence of disinvestment and gentrification—especially in North Minneapolis.

Two zip codes in North Minneapolis (55411 and 55412) account for about 8% of the city’s population—but 35% of the city’s evictions. In fact, from 2013-15, a staggering 50% of renter households in those two zip codes experienced eviction. Dr. Lewis interviewed dozens of renters and landlords to better understand why this was happening. Her groundbreaking report, The Illusion of Choice: Evictions and Profit in North Minneapolis, illuminates how we got into this eviction crisis.

And it all comes back to disinvestment.

“The history of disinvestment, from redlining on, created the north side,” Dr. Lewis says. “It created a place where outside investors, most of whom are white and male, can buy at the lowest price, not fix up shit, and make more profit than the person who is building a condo downtown.”

Dr. Lewis’ team found that all landlords interviewed had identified cheap acquisition cost as a top reason for becoming landlords in North Minneapolis. Almost half of them became landlords in the last 10 years, the majority buying homes in the wake of the 2008 foreclosure crisis. The vast majority don’t live in the neighborhood, so rental dollars don’t circulate through the community. And many said they didn’t have construction or management experience, and simply “fell into” becoming a landlord as an investment opportunity.

When Dr. Lewis’ team interviewed renters in these focus neighborhoods, they found that the majority felt like they had no true choice in where they lived. Tenants often put up with serious housing and health issues because they were afraid of evictions making them homeless. While housing assistance is available for some, the “runaround” of completing requirements and tracking forms can become an almost part-time job for tenants. Most described it as “dehumanizing.”

This video shares stories from "The Illusion of Choice" report. Watch to hear stories from landlords and tenants who participated in the study. Video from the Center for Urban & Regional Affairs (CURA).

“I would argue that the history of disinvestment created that context,” says Dr. Lewis. “The question I throw to everyone I work with is how do we move past equity-based language to equity-based actions.”

That’s why Dr. Lewis’ work is so important. She’s learned that lawmakers always want research before making big policy changes. So she conducts the important research in partnership with the folks who will be most impacted. Instead of talking at people, Dr. Lewis listens closely and amplifies their voices.

It’s on all of us to learn this history, hear how this cycle of disinvestment impacts our neighbors, and advocate for change. Check out our Race & Housing Resource Center to read more about the history of racism in housing policies.

Your gift unlocks bright futures! Donate now to create, preserve, and promote affordable homeownership in the Twin Cities.

Twin Cities Habitat has a core valueof Equity and Inclusion which states: “We promote racial equity and strive to increase diversity, inclusion, and...

Twin Cities Habitat for Humanity supports Cost of Home, a national campaign to expand housing affordability for ten million people in the next five...

Most people don’t think much about the intersection of racism and the home appraisal process, but systemic racism still exists in housing and the...